This chapter seemed to take forever to work through, possibly because a bit of life stuff came up in the interim but it’s also at the more complex end of the discussion. It concludes the overall examination of the dynamics of social practice and in some ways felt like a boss level that I’d been working up to. Most of the chapter made sense but I must confess that there is a page about cross-referencing practices as entities that I only wrote “wut?” on in my notes. Maybe it’ll make more sense down the road.

The good news is that there was more than enough more meaningful content in this chapter to illuminate my own exploration of practices in my research and it sparked a few new stray ideas for future directions. There’s a decent summary near the end of the chapter that I’ll start with and then expand upon. (The authors do great work with their summaries, bless them)

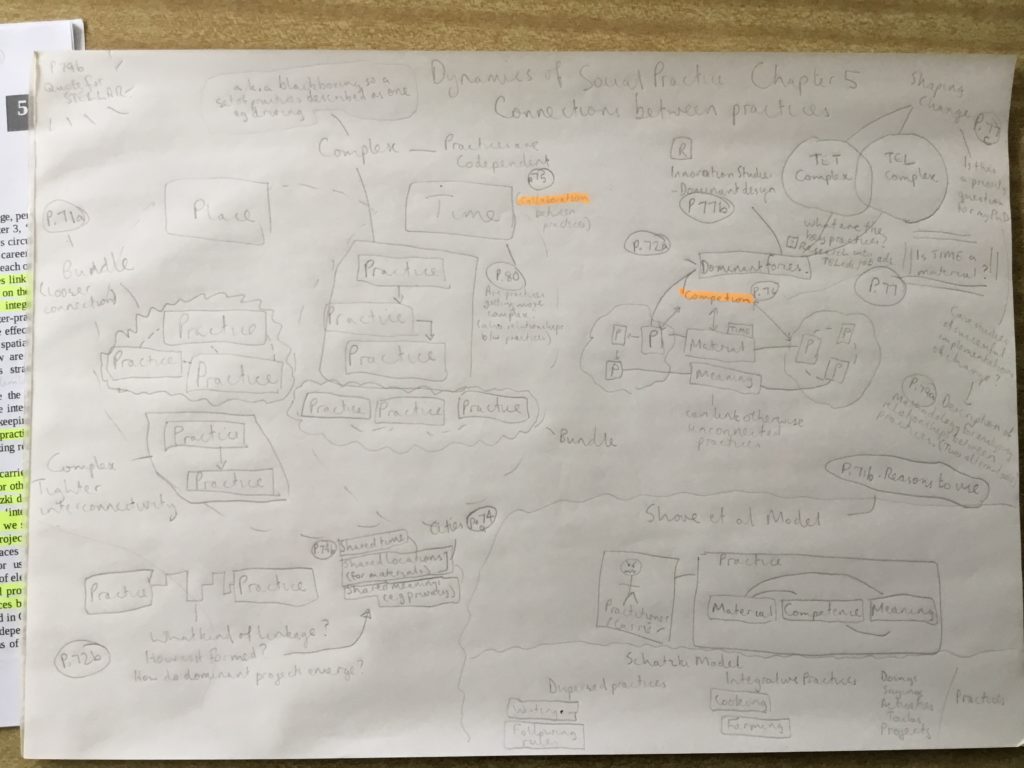

In this chapter we have built on the idea that if practices are to endure, the elements of which they are made need to be linked together consistently and recurrently over time (circuit 1). How this works out is, in turn, limited and shaped by the intended and unintended consequences of previous and co-existing configurations (circuit 2). Our third step has been to suggest that persistence and change depend upon feedback between one instance or moment of enactment and another, and on patterns of mutual influence between co-existing practices (circuit 3). It is through these three intersecting circuits that practices-as-entities come into being and through these that they are transformed. (p.93)

So let’s unpack this a little. There are a number of reciprocal relationships and cycles in the lives of practices. The authors discuss these in two main ways – through the impact of monitoring/feedback on practices (both as individual performances and larger entities) and also by cross-referencing different practices (again as performances and entities)

Monitoring practices as performances

A performance of a practice will generate data that can be monitored. It might be monitored by the practitioner (as a part of the practice) and it might also be monitored by an external actor that is assessing the performance or the results/outputs. (This might be in an education/training context or regulatory or something else). This monitoring then informs feedback which improves/modifies that performance and/or the next one/s and so the cycle continues. In some way, potentially, in every new performance, the history of past performances can help refine the practice over time.

This isn’t all that evolves the practice; materials, competences and meanings play their part too, but it is a significant factor.

Monitoring, whether instant or delayed, provides practitioners with feedback on the outcomes and qualities of past performance. To the extent that this feeds forward into what they do next it is significant for the persistence, transformation and decay of the practices concerned… self-monitoring or monitoring by others is part of, and not somehow outside, the enactment of a practice (what are the minimum conditions of the practice?) is, in a sense, integral to the performance. Amongst other things, this means that the instruments of recording (the body, the score sheet, the trainee’s CV) have a constitutive and not an innocent role. (p.83-4)

So far, so good. This also makes me think that many practices are made up of elements or units of practice – let’s call them steps for simplicity. The act of monitoring is just another step. (This does take us into the question of whether it is a practice or a complex/bundle of practices – like driving is made up of steering, accelerating, braking, signalling etc – but nobody says they’re going out accelerating)

Monitoring practices as entities

Looking at a practice as an entity is to look much more at the bigger picture of the practice.

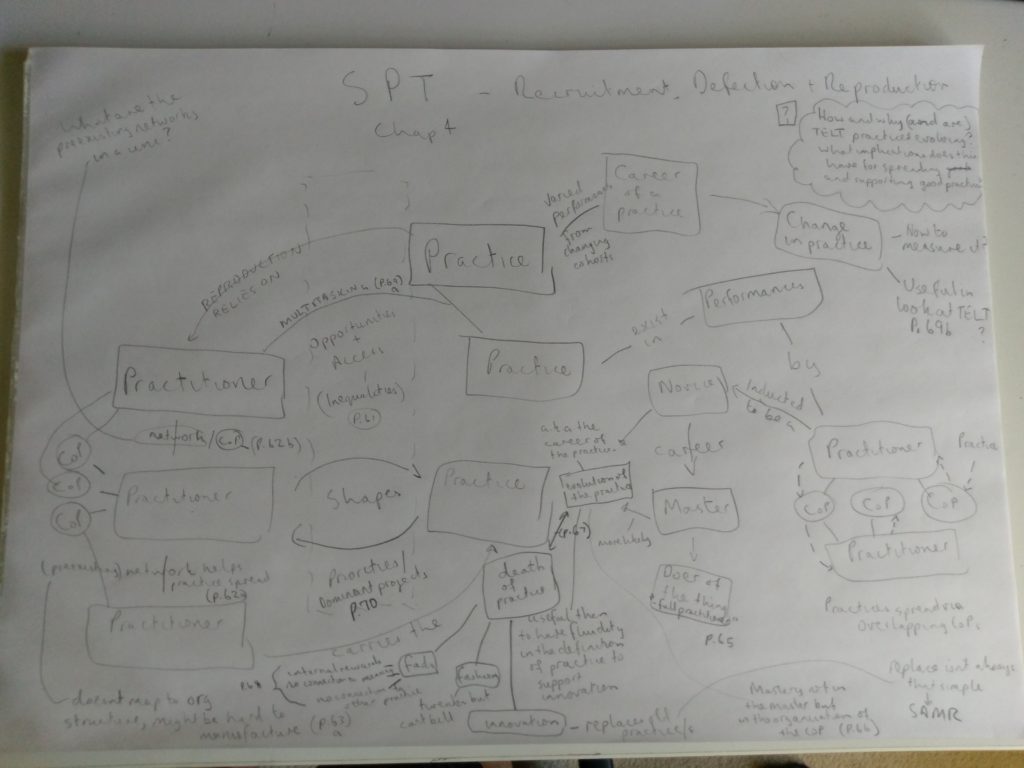

the changing contours of practices-as-entities are shaped by the sum total of what practitioners do, by the variously faithful ways in which performances are enacted over time and by the scale and commitment of the cohorts involved. We also noticed that practices-as-entities develop as streams of consistently faithful and innovative performances intersect. This makes sense, but how are the transformative effects of such encounters played out? More specifically, how are definitions and understandings of what it is to do a practice mediated and shared, and how do such representations change over time (p.84)

An interesting side-note when considering the evolution of practice is the contribution of business. This example was in a discussion of snow-boarding

As the number of snowboarders rose, established commercial interests latched on to the opportunities this presented for product development and profit (p.85)

This ties back to the influence of material elements (new designs and products in this case) on shaping a practice.

Technologies are themselves important in stabilising and transforming the contours of a practice. In producing snowboards of different length, weight, width and form, the industry caters to – and in a sense produces – the increasingly diverse needs of a different types of user… Developments of this kind contribute to the ongoing setting and re-setting of conventions and standards. (p.85)

This in turn brings up back to one of the other key roles played by monitoring (and feedback) in terms of practices as entities, which is describing and defining them. The language that is used to describe a practice and its component parts and also to define what makes good practice is of vital importance in determining what a practice is and what it becomes.

…if we are to understand what snowboarding ‘is’ at any one moment, and if we are to figure out how the image and the substance of the sport evolves, we need to identify the means by which different versions of the practice-as-entity relate to each other over time. Methods of naming and recording constitute one form of connective tissue. In naming tricks like the ollie, the nollie, the rippey flip and the chicken salad, snowboarders recognise and temporarily stabilize specific moves. Such descriptions map onto templates of performance- to an idea of what it is to do an ollie, and what it means to do one well… in valuing certain skills and qualities above others, they define the present state of play and the direction in which techniques and technologies evolve. (p.85)

So clearly, monitoring and description and standardisation/regulation and the dissemination of all of this is hugely important on practices. Interestingly, a Community of Practice for TEL edvisors that I’ve started recently had our first webinar yesterday looking at the different standards that Australian universities have for online course design. It probably merits a blog post of its own but I guess it’s a good example of what needs to happen to improve Technology Enhanced Learning and Teaching practices.

The final piece of the puzzle when it comes to monitoring – which ties back to our webinar nicely once more – is mediation.

Describing and materializing represent two modes of monitoring in the sense that they capture and to some extent formalize aspects of performance in terms of which subsequent enactments are defined and differentiated. A third mode lies in processes of mediation which also constitute channels of circulation. Within some snowboarding subcultures, making and sharing videos has become part of the experience. These films, along with magazines, websites and exhibitions, provide tangible records of individual performance and collectively reflect changing meanings of the sport within and between its various forms. Put simply, they allow actual and potential practitioners to ‘keep up’ with what is happening at the practice’s leading edge(s) (p.86)

I find the fact that monitoring/documenting and sharing the practice is considered an important part of practice quite interesting. Looking at teaching, I’ve tried to launch projects to support this in teaching but management levels have not seen value in this. (I’ll just have to persevere and keep making the argument).

There’s another nice description of the role of standards

…standards, in the form of rules, descriptions, materials and representations, constitute templates and benchmarks in terms of which present performances are evaluated and in relation to which future variants develop (p.86)

The discussion of the role of feedback notes that positive feedback can be self-perpetuating, in “what Latour and Woolgar refer to as ‘cycles of credibility’ (1986). Their study of laboratory life showed how the currencies of scientific research – citations, reputation, research funding – fuelled each other. In the situations they describe, research funding led to research papers that enhanced reputations in ways which made it easier to get more research funding and so on” (p.86)

Ultimately, feedback helps to sustain practices (as entities) by keeping practitioners motivated.

At a very basic level, it’s good to know you are doing well. Even the most casual forms of monitoring reveal (and in a sense constitute) levels of performance. In this role, signs of progress are often important in encouraging further effort and investment of time and energy (Sudnow, 1993). The details of how performances are evaluated (when how often, by whom) consequently structure the careers of individual practitioners and the career path that the practice itself affords. This internal structure is itself of relevance for the number of practitioners involved and the extent of their commitment (p.86)

Cross-referencing practices-as-performances

The act of participating in a performance of a practice means that it has been prioritised over other practices – the time spent on this performance is not available to the others.

…some households deliberately rush parts of the day in order to create unhurried periods of ‘quality’ time elsewhere in their schedule. In effect, short-cuts and compromises in the performance of certain practices are accepted because they allow for the ‘proper’ enactment of others (p.87)

Shove et al examine the importance of time as a tool, a coordinating agent that helps in this process. In a nutshell, it is a vital element of every practice and shapes the interactions between practices (and also practitioners). They move on to explore the change from static ‘clock-time’ to a more flexible ‘mobile-time’. Their argument is essentially that our adoption of mobile communication technologies (i.e. smart phones) is giving us a more fluid relationship with time because we can now call people on the fly to tell them that we are running late.

However some commentators are interested in the ways in which mobile messaging (texting, phoning, mobile emailing) influences synchronous cross-referencing between practices (p.88)

I’ll accept that mobile communication is changing the way we live but I’m not convinced that it is having the impact on practices that the authors suggest. Letting someone know that you’re running late particularly doesn’t change what is to be done, it just pushes it back. Perhaps letting someone know of a change of venue has more impact, in that it would allow a practice that might not otherwise have occurred to do so, but this doesn’t strike me as something that would happen regularly enough to change our concepts of time or practice.

The authors express this somewhat more eloquently than I:

But is this of further significance for the ways in which practices shape each other? For example, does the possibility of instant adjustment increase the range of practices in which many people are involved? Does real-time coordination generate more or less leeway in the timing and sequencing of what people do? Are patterns of inattention and disengagement changing as practices are dropped or cut short in response to news that something else is going on? Equally, are novel practices developing as a result? In thinking about these questions it is important to consider how technologies of ‘micro’-coordination relate to those that operate on a global scale (p.89)

Another significant idea that this generated for me was that the things that we do shape our world because we design and modify our world to suit the things that we do. This then may change our ability to do those things and we enter a cycle where practice shapes environment shapes practice etc.

Or as the authors put it:

we have shown that moments of performance reproduce and reflect qualities of spacing and timing, some proximate, some remote. It is in this sense that individual practices ‘make’ the environments that others inhabit (p.89)

I guess then, the real question is how we as TEL edvisors can make this work for us.

Cross-referencing practices-as-entities

This is the section that lost me a little but parts made sense. It’s something to do with the way that separate practices might be aggregated as part of a larger issue – such as eating and exercise both sit within this issue of obesity. Clearly obesity isn’t a practice but it does encompass both of these practices and creates linkages that wouldn’t necessarily otherwise be there. This happens in part by tying in monitoring and creating a discourse/meaning attached to them all.

The authors refer to this combination of the discourse and the monitoring via measurement technologies as “epistemic objects, in terms of which practices are conjoined and associated, one to another” (p.92). (And arguably monitoring and discourse create their own cyclical relationship)

They move on to expand the significance of the elements of a practice (material, competence and meaning),

this time viewing them as instruments of coordination. In their role as aggregators, accumulators, relays and vehicles, elements are more than necessary building blocks: they are also relevant for the manner in which practices relate to each other and for how these relations change over time. (p.92)

Writing and reading – as competences rather than practices I guess – occupy a vital space here in terms of the ways that they are vital in the dissemination of practices, meanings and techniques.

They discuss two competing ideas by other scholars in the field (Law and Latour) that posit that either practices need elements to remain stable for significant periods of time to allow practices to become entrenched or that they benefit from changes in the elements that enable practices to evolve. I don’t actually think that these positions are mutually exclusive.

Other thoughts

I jotted down a number of stray thoughts as I read this chapter that don’t necessarily tie to specific sections, so I’ll just share them as is.

Is a technology a material or does it also carry meanings and competences?

Does research culture/practice negatively impact teaching practice? Isolated and competitive – essentially the antithesis of a good teaching culture.

Does imposter syndrome (in H.E. specifically) inhibit teachers from being monitored/observed for feedback? Does rewarding only teaching excellence inhibit academic professional development in teaching because it stops people from admitting that they could use help. Are teaching excellence awards a hangover from a research culture that is highly competitive?

What if we could offer academics opportunities to anonymously and invisibly self assess their teaching and online course design?

Is Digigogy (digital pedagogy) the ‘wicked problem’ that I’m trying to resolve in my research – in the same way that ‘obesity’ is an aggregator for exercise and eating as practices? I do like ‘digigogy’ as an umbrella term for TEL practices.

Where do TEL edvisors sit in the ‘monitoring’ space of TEL practices?

This ‘epistemic objects – cycle of monitoring/feedback and discourse’ is probably going to play a part in my research somehow. Maybe in CoPs.

So what am I taking away from this?

I guess it’s mainly that there are a lot of different ways in which practices (and performances of practices) are connected which impact on how the evolve and spread. Monitoring and feedback – particularly when it is baked into the practice – is a big deal. The whole mobile time thing feels like an interesting diversion but the place of technology (and what exactly it is in practice element terms) will be a factor, given that I’m looking at Tech Enhanced Learning. (To be honest though, I think I’m really looking at Tech Enhanced Teaching)

In specific terms, it seems more and more like what I need to do is break down all of the individual tasks/activities that make up the practice of ‘teaching’ – or Tech Enhanced Learning and Teaching – and find the cross-over points with the activities that make up the practice of a TEL edvisor. I think there is also merit in looking at the competition between the practices of research for academics and teaching, which impacts their practice in significant ways.

On now to Chapter 7, where the authors promise to bring all the ideas together. Looking forward to it.

2977232

{:N6MUK7MP}

apa

50

992

https://www.gamerlearner.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/