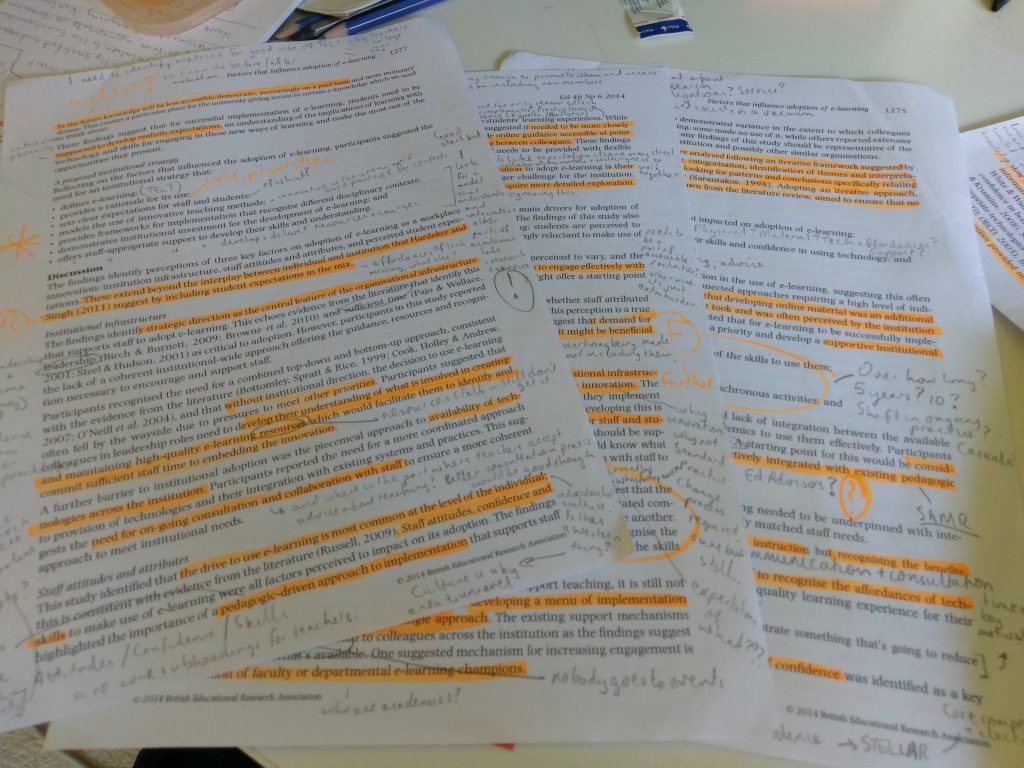

I’ve been really struggling to process my thoughts on this paper for the last week. I’ll read a few pages, furiously scribbling notes all over it, and then need to step away to deal with my responses to it.

Now this isn’t particularly uncommon for me as it helps me feel that I’m part of a discourse and I try to create action items for future followup, particularly with citations. It often also feels like the most convenient place to jot down other ideas, like the spectrum of edvisor practices that I’ve started on the bottom of page two there. But I think I’ve probably written more on this paper than most because while I agree with most of the broad principles, the lack of understanding that it demonstrates of the practices of academic development and the capacity of academic developers to effect significant change in the institution undercuts much of what it has to say. Which surprises and disappoints me, particularly because I’ve spoken to one of the authors on several occasions and have great respect for his other work and I’ve read many of the other author’s papers and hold her in similar esteem. She has also, according to her bio, worked as an academic developer and co-edited the academic journal that this paper appears in, which makes it even harder to understand some of the misperceptions of this kind of work.

Which leads me to question my own perceptions. Am I overly defensive about what feels like an attack of the competence and professionalism of my colleagues and I? Is the environment that I work in uniquely different and my attitudes towards the development of academics that far out of the norm suggested by this paper? Perhaps most importantly am I taking this too personally and is my emotional response out of proportion to the ideas in the paper?

I suspect that part of my frustration is that the paper begins by talking about something which sounds like academic development but which ends up being a call for a complete revision of all aspects of academic practice and an implication that academic developers should really do something about that.

Assuming that academic development or academic developers are even actually necessary in the first place. There are a couple of telling remarks that, to me at least, strongly imply that academic development is a cynical exercise by university management to impose training on an academic staff that doesn’t need it – they did a PhD after all – in the interests of ensuring compliance with organisational policy and being seen to do something.

Or to put it another way (emphasis mine):

The development of academics is based on the notion that institutions need to provide opportunities for their academic employees to develop across a range of roles. Any initial training (e.g. through undertaking a PhD) is not sufficient for them to be able to meet the complex and increasing demands of the modern academy. Their development is an essentially pragmatic enterprise aimed at making an impact on academics and their work, prompted by perceptions that change is needed. This change has been stimulated variously by: varying needs and a greater diversity of students, external policy initiatives, accountability pressures and organisational desires to be seen to attend to the development of personnel. (p.208)

“Varying needs” almost seems to be used as a get-out-of-jail free card for those apparently rare instances where an academic might benefit from some additional training to be able to meet their responsibilities in teaching, research, service and potentially management.

There’s another section where the authors discuss the challenges of academic development. It’s close to a page long – 4 solid paragraphs, 22 lengthy sentences – yet it lacks a single citation to support any of the assertions that the authors make. The main argument made is that academic developers (and their units) don’t provide academics with the development that will help them because the developers are beholden to the agendas of the institution. The same institution, I should mention, that is governed at an executive level by senior academics who presumably have a deep understanding of academic practices.

Like most forms of education and training, academic development is continually at risk from what might be termed ‘provider-capture’, that is, it becomes driven by the needs of the providers and those who sponsor them, rather than the needs of beneficiaries’ (p. 210)

The main objection that the authors appear to have is that the institution takes a simplistic approach to training – because, reasons? – that implies that academics don’t already know everything that they need to.

…academic development has a tendency to adopt a deficit model. It assumes that the professionals subject to provision lack something that needs to be remedied; their awareness needs to be raised and new skills and knowledge made available. The assumption underpinning this is that without intervention, the deficit will not be addressed and academics not developed. (p.210)

Correct me if I’m wrong but I suspect that this is precisely the attitude that lies at the heart of the teaching practices of many academics. The students need knowledge/skills/experience in the discipline and its practices and the teacher will help them to attain this. Is the implication that academics deserve to be developed better than their students? Does it suggest a deficit in the pedagogical knowledge of academics? I would argue that this description undervalues the sophistication of work done by both academics and academic developers. Which the authors hypothetically note but then immediately discount based upon…? (Emphasis mine)

Such a characteristation, many developers would protest, does not represent what they do. They would argue that they are assiduous in consulting those affected by what they do, they collect good data on the performance of programmes and they adjust what they do in the light of feedback…they include opportunities for academics to address issues in their own teaching, to research their students’ learning and to engage in critical reflection on their practice. Developers undoubtedly cultivate high levels of skill in communicating and articulating their activities for such a demanding group. Nevertheless they are positioned within their institutions to do what is required of them by their organisation, not by those they claim to serve. (p.210-211)

It’s hard to go past “those affected by what they do” as an indicator of the attitudes towards academic developers. I’d also make the point that I’ve come across few institutions with a comprehensive, practical strategy on teaching and learning and it generally falls on academic developers to use their extensive professional knowledge and experience to offer the best advice and support available in the absence of this.

The other significant point that I feel that the authors have completely missed – again perhaps surprisingly given their experience – is that, in my experience at least, academic professional development is almost never mandated and simply getting academics to attend PD is a task unto itself. The authors must certainly be aware of this, having written a recent paper (2017) that I found invaluable about academic responses to institutional initiatives. (Spoiler alert, it’s like herding sleeping cats). Academic developers are painfully aware of this – imagine spending days preparing a workshop or seminar only to have two attendees – and this if nothing else necessitates design of PD activities that are as relevant and attractive to academics as possible. I won’t dispute that the further away academic development teams are from academics – e.g. centralised teams – the harder it can be to do this and the more generic content becomes but even these areas have a deeper understanding of academics and their needs than is implied. (And I still have more to say about the practical realities of delivering PD that can wait for now)

Now that we’ve gotten past that – and it was something that I evidently needed to say – we start to get to the nub of what the authors would prefer instead of this ‘deficit model’.

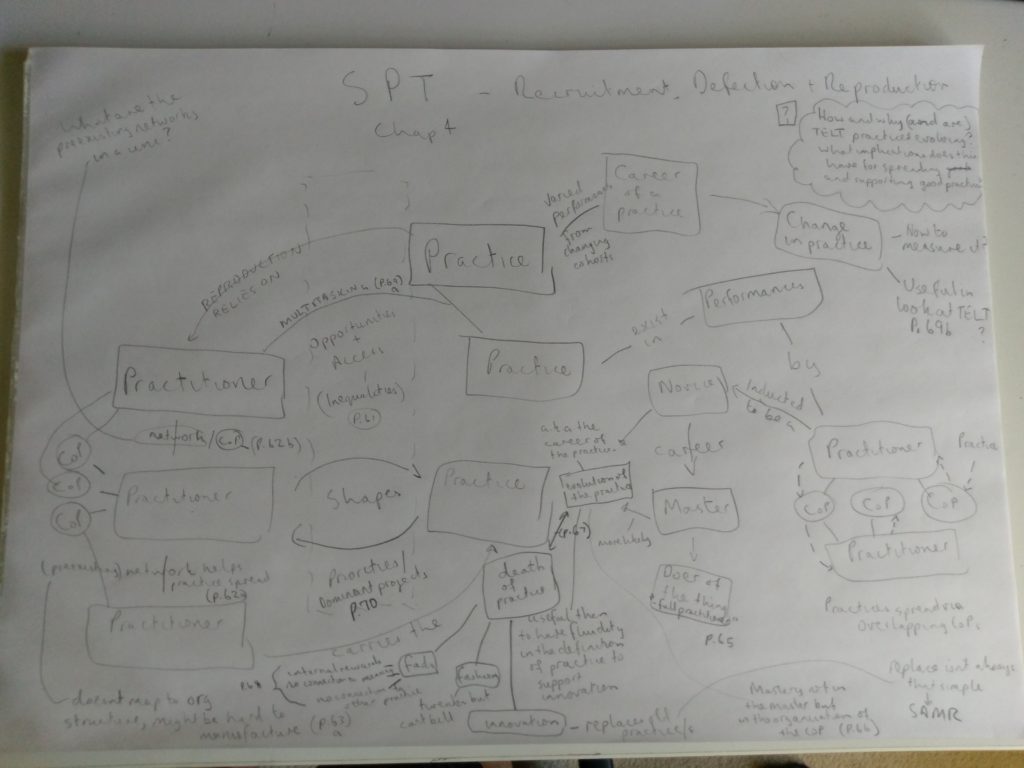

The authors draw on Schatzki’s (2001) work in Social Practice theory, which is an area that I’ve spent some time looking at and which I see the value of. My introduction came through the work of Shove et al (2012) who present a slightly different perspective, a more streamlined one perhaps, but fundamentally the same. Where Shove et al identify three major elements to practice – meaning, materials and competences, Schatzki is a little more granular and includes elements such as emotions/moods, projects, tasks and ends. Arguably these could sit in the three elements of Shove et al but there might be something in looking more deeply at emotions/moods particularly. Maybe I’ll end up taking a Shovezki based approach to practice theory.

At the risk of oversimplifying it, from what I can see practice theory necessitates taking a more holistic perspective of being an academic and recognising that the different practices in the bundle of practices (or is it a complex – one or the other) that make up “being an academic” all occur in a specific context involving the practitioner, time, space and the larger meaning around what is being done. These sub-practices – such as teaching, research, service – can be in competition with each other and it is necessary to factor them in when providing PD training that relates to any other of them. Now this is an avenue of thinking that I’ve been pursuing myself, so obviously I’m pretty happy with this part of the paper. When we look at why an academic doesn’t undertake an activity to enhance their teaching, the current research rarely seems to answer – ‘well it was partially because they had to put together an application for research funding and that took priority’. This much I appreciate in the paper.

Where I think the paper runs into trouble though is that it makes a case for a slightly hazy approach to re-seeing academics practices as a whole, taking into consideration the following six factors that shape them:

-

Embodiment – “It is the whole person who engages in practice, not just their intellect or skills… Desires, emotions and values are ever present and cannot be separated out” (p.212)

-

Material mediation – “Practice is undertaking in conjunction with material arrangements. These may include objects such as raw materials, resources, artefacts and tools, physical connections, communication tools, organisms and material circumstances (Kemmis, 2009). These materials can both limit and enable particular practices” (p.212)

-

Relationality – “Practice occurs in relation to others who practice, and in relation to the unique features a particular practitioner brings to a situation. Practice is thus embedded in sets of dynamic social interactions, connections, arrangements, and relationships” (p.212)

-

Situatedness – This I’d call context – “…in particular settings, in time, in language… shaped by mediating conditions…” that “may include cultures, discourses, social and political structures, and material conditions in which a practice is situated” (p.213)

-

Emergence – “Practices evolve over time and over contexts: new challenges require new ways of practising” (p.213)

-

Co-construction – “Practices are co-constructed with others. That is, the meaning given to practice is the meaning that those involved give it” (p.213)

In my personal experience, I don’t believe that many academics give their practices, particularly teaching, anywhere near this level of reflection. It’s probably fair to say that few academic developers would either, at least not consciously. The authors believe that using this new practice frame

“…moves academic development from a focus on individuals and learning needs to academic practice and practice needs; from what academics need to know to what they do to enact their work” (p.213-214)

Maybe it’s just my professional background but I think that I pretty well always frame learning objectives in terms of the tangible things that they need to be able to do. On the other hand, my experience with academics is largely that many of their learning outcomes for their students begin with “understand x” or “appreciate the concept of y”. It’s not my job to be a discipline expert and I have no doubt that these are important learning outcomes to the academics – and I might still be misinterpreting how the authors are thinking about practices and learning design.

They go on to make an important point about the value of situated learning in professional development – conducting it in the space where the teacher teaches rather than in a removed seminar room in a building that they never otherwise visit. This makes me think that it would be valuable to have a simulated workspace for our students to learn in and I’ll give that some more thought but the logistics seem challenging at the moment as we undergo massive redevelopment. (This also acts as a pretty significant barrier to providing situated professional development, as teaching spaces are occupied from 8am to 9pm every day).

There’s an additional idea about the format of assessment conducted by ADs and what more beneficial alternatives might be considered.

“Learning is driven by, for example, by encountering new groups of students with different needs and expectations, or by working with a new issue not previously identified. Success in learning is judged by how successfully the practice with the new group or new issue is undertaken, not by how much is learnt by the individuals involved that could be tested by formal assessment practices” (p.214)

I completely support this approach to learning but I cannot see how it could ever be implemented with current staffing levels. If we’re going to think seriously about practices in an holistic way, perhaps a wider view needs to be taken that encompasses all of the participants in co-construction of the practice. This is probably where I think that this paper falls down heaviest – there seems to be a wilful blindness to ability to enact these new approaches. I also don’t see any academics ever moving to this kind of approach in their own teaching for the exact same reason.

This brings me to my larger challenge with this paper – from here (and perhaps in ignoring the logistical issues of situated learning in teaching spaces), there seems to be an expectation that it is up to academic developers and/or their units to make a lot of these significant changes happen. I can only imagine that this comes from the openly held perception that ADs are tools of ‘university management’ – which I will stress yet again is made up of academics – and that ADs are able to use these connections to management to effect major changes in the institution. I’m just going to quote briefly some of these proposed changes because I think it is self-evident how absurd that would be to expect ADs to implement any of them.

We suggest that a practice perspective would thus place greater emphasis on the development of academics:

…

(2) as fostering learning conducive work, where ‘normal’ academic work practices are reconfigured to ensure that they foster practice development; (p.214)

And this

“Working with individual academics to meet institutional imperatives, for example, curriculum reform, comes up against various stumbling blocks where academics complain that they are overworked, that there is too much to take on and that their colleagues are not supportive of what they are trying to do. Practice development means working with how that group juggles various aspects of their role and their attitudes and beliefs in relation to that. It is about how the group interacts in pursuing its practice, how and where interpersonal relationships are take account of the being of its members, how power and authority are negotiated, whose ideas are listened to and taken up and whose are denied” (P.215)

So, I’ll change the entire culture of academia and then after lunch… I know that sounds cynical but if the VC can’t enact that kind of a mindset shift…

I don’t disagree with any of these changes by the way but even in my relatively short time in the H.E. sector I have had it made painfully clear to me that the expertise of professional staff is basically never considered in these processes, so this paper is wildly misdirected.

The paper wraps up with a few more achievable suggestions that I think ADs have known for a long time already and try to enact when possible. Offering training or advice about something (e.g the grading system in the LMS) is going to be more valuable in some temporal contexts (weeks of semester) than others, learning more about academics and their particular practice needs – again, generally teaching as I suspect there is hierarchy of things that academics never want to have their knowledge questioned on – discipline knowledge, research skills, teaching and then technology. I might look into how often academics go to research training after they finish PhDs. I suspect it will be rarely – but I don’t know. (I should probably know that)

The authors also suggest that ADs might take a project based approach, a consultancy one or a reflective one to their development work and I would consider that communities of practice probably sit well with the latter.

Ultimately, while I am broadly supportive of many of the approaches and the more holistic viewpoint put forward in this paper, expecting ADs to implement many of the larger changes seems to demonstrate a lack of awareness of the powerlessness of people in these kinds of roles. What is proposed would largely require a significant cultural shift and to be driven from the top. Of course, the latter paper by Brew, Boud et al (2017) shows the utter folly of expecting that to succeed.