Given that people are at the heart of implementing and supporting TELT practices in Higher Education, I’ve been investigating the kinds of people involved.

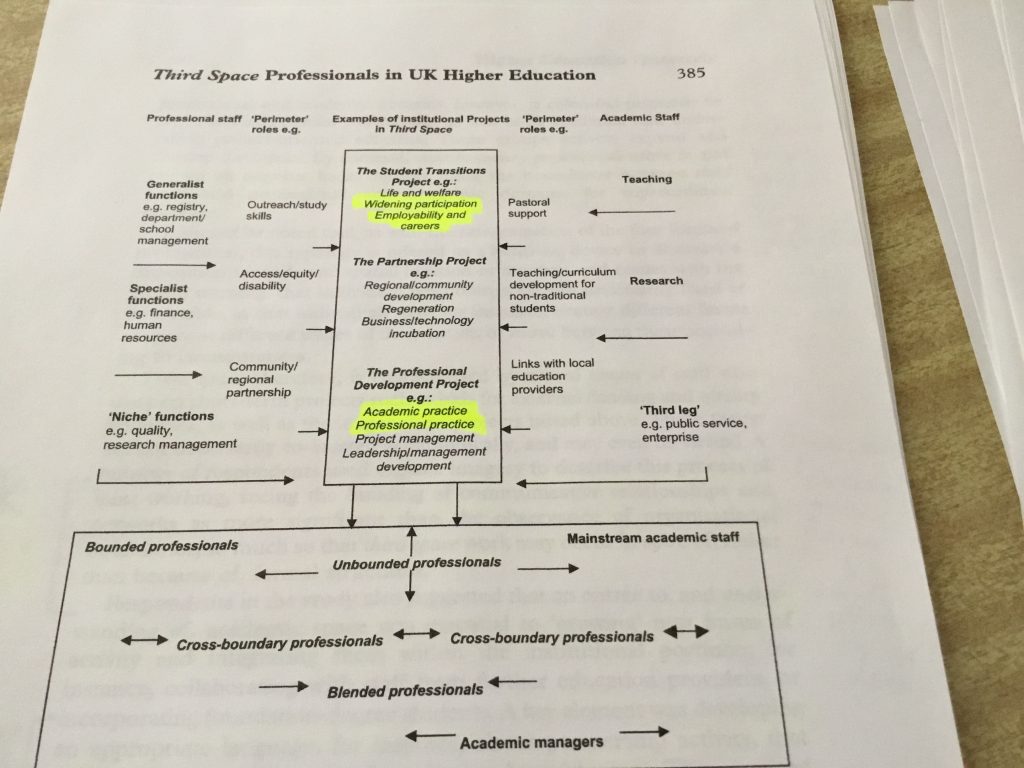

At the first level of the taxonomy, universities employ academic and professional staff. Whitchurch (2008) makes a solid case that, while these people generally work in their own domains, there are people who work across these boundaries in different ways – third space professionals. For the sake of simplicity however, and also because the three papers that I read focus almost entirely on ‘administrative’ professional staff, I’m just going to examine the key differences and some of the sources of tension between these two groups.

Following on from the paper I posted about recently by Jones et al (2012) on Distributed Leadership, I dove down the rabbit hole of citations and found these three papers:

Mcinnis, C. (1998). Academics and Professional Administrators in Australian Universities: dissolving boundaries and new tensions. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 20(2), 161–173. http://doi.org/10.1080/1360080980200204

Dobson, I. R. (2000). “Them and Us” – General and Non-General Staff in Higher Education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 22(2), 203–210. http://doi.org/10.1080/713678142

Szekeres, J. (2004). The invisible workers. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 26(1), 7–22. http://doi.org/10.1080/1360080042000182500

The first thing I noticed after reading all three papers was the small ways in which the writers’ personalities, assumptions and perspectives creep through. In some ways, they reflect the larger issues at hand, occupying a spectrum from begrudging acceptance of the need to take professional staff more seriously within set parameters to good-natured concern at the disregard of them to simmering disquiet at the routine slights experienced (mixed in with a distaste for the Neoliberalism that has been a part of many recent changes in Higher Ed. and exacerbated these divisions)

Collectively they all seem to arrive at more or less the same destination – that greater understanding is needed about the roles and values of professional staff and academics and that more needs to be done to foster better collaboration. The differences in how they get there and what they believe is needed to help this to happen (and why) are illustrative of the issues themselves.

McInnis and Dobson were (and are) academics and Szekeres was a professional administrative staff member – also working on her doctorate at the time. Their respective positions in their universities offer additional insights into different attitudes in different departments – McInnis working as an Associate Professor in a school and Dobson holding a role tied to the executive.

The three papers were written in a reasonably narrow window of time – 1998 to 2004 – when Australian universities were still coming to terms with major shifts to the sector introduced by John Dawkins (Federal minister responsible for Higher Education) in the mid to late ’80s. These heralded a more market driven and corporate managerialist mindset in public institutions. (More on this shortly)

The language used in all of these papers is interesting in itself, the now commonly used “professional staff” terminology is nowhere to be seen, the terms of the day were administrative staff, general staff or non-academic staff. Being academia, these terms were also picked apart for their own implied meanings and values – with “non-academic” given special attention for seeking to define people by what they aren’t.

Dobson particularly is very mindful of this, titling his paper “Them and Us – General and Non-General staff in Higher Education”, turning the tables on the usual academic / non-academic binary. He comments that

“the tendency to describe general staff in this negative way is a strange trait in the current climate of inclusiveness promoted fairly generally by universities, but in particular by universities’ acceptance of equity and affirmative action principles” (p.203)

Dobson and Szekeres’ papers are largely based around a review of the current literature (including government and university reports, letters to H.E. publications and novels) as well as informal notes from conversations with colleagues overseas. McInnis takes a different approach, comparing the results of two surveys of attitudes conducted of academics and administrative staff (at a management level).

All agree that there are a number of differences and tensions between academic and professional staff and recognise that professional staff are massively underrepresented in discussions and publications relating to Higher Education.

(I’m curious to see whether this is still the case – I imagine it is, based on my own experiences – and have flagged it for further research). At this point I need to mention that I was initially looking more for writing about Education Support Professionals and the nature of their relationships with academics but there is scant reference to this role in any of these papers. McInnis mentions that

“Professional administrators are reshaping academic work by virtue of their increasingly pivotal roles in such areas as course management and delivery” (p.168)

but the emphasis here is much more on people working in non-teaching areas of the university, or as Szekeres more comprehensively puts it

“their focus is about either supporting the work of academic staff, dealing with students on non-academic matters or working in an administrative function such as finance, human resources, marketing, public relations, business development, student administration, academic administration, library, information technology, capital or property” (p.8)

Even though in these papers we are looking at people working in “non-academic” areas, I think there is still much to be learned from exploring the broader relationships between academics and professionals as it is often people working in professional roles that are charged with supporting and initiating TELT practices in Higher Ed. Putting aside the boundary crossing tendencies of this relationship and the complications that arise from stepping onto teaching and learning ‘turf’, there are many other moving parts to be considered and these three papers offer valuable insights into other facets of this relationship, particularly university culture.

The virtual absence of professional staff in the literature discussing people working in Higher Education is recognised by all three authors here. Szekere’s paper title – “The Invisible Workers” – is a pointed reminder of this and even in the defining documents of the time (Dawkins’ Green and White papers) Dobson notes that

“general staff were scarcely considered during the writing of the Green Paper. In fact there are only three paragraphs devoted to the subject” (p.204)

This lack of presence in literature (of all kinds) discussing Higher Ed illustrates one of the interesting contradictions of the relationship between professionals and academics – the work and expertise of professionals is misunderstood and considered trivial but they also represent a threat to the status quo (of academic values) in terms of the change that they represent and they are felt (by academics) to hold too much power. Maybe the hope is that by not talking about them, they will just go away or maybe academics simply have a blind spot to people not in their ‘tribe’. (Neither of those are points raised by any of the authors)

Szekeres raises another factor in discussing invisibility, that of gender, pointing out that

“while women make up the majority of general staff, they are disproportionately in the lower-level positions” (p.8)

Again, I’d hope that more recent research will show that this has changed but I won’t be surprised if it hasn’t. Dobson discusses a study carried out by UWA on “The Position of Women General Staff at the University of Western Australia” that aimed to

“identify any cultural or structural impediments within the University which might work against the aspirations of women and propose strategies to address these. (UWA, Executive Summary, P.1)” (p.206)

It found that

“the issue of gender was less of a barrier to their aspirations than the fact that they were members of the general staff” (p.206)

This is not at all to say that there aren’t issues faced specifically by professional women in Higher Ed, simply that the professional/academic divide is a significant one.

At the heart of the divide lies the aforementioned culture of corporate managerialism. This ties in to new practices, changes to decision making structures and moves toward greater accountability and efficiency that can come into conflict with the established ‘academic values’, university culture and autonomy that make Higher Education a distinct sector.

Szekeres describes the rise of this culture of corporate managerialism particularly well:

‘As pressure increases on governments to account for the expenditure of public funds, they respond either by privatising government institutions or by increasing the reporting requirements of those few public institutions left…

In many texts, this increase of surveillance and privatisation is characterised as a neoliberal agenda. It exhibits itself through public institutions remodeling themselves along commercial lines and falls into a general discourse, corporate managerialism. This discourse has a number of elements including: an increase in managerial control (managerialism); competing with each other in the marketplace (marketization); being under greater scrutiny while having greater devolved responsibility (audit); and generally modelling their structures and operations on corporate organisations (corporatisation)” (p.9)

This kind of change can’t occur without at least perceived winners and losers. McInnis’ discussion of the two attitude surveys of academics and administrative staff, taken relatively early in the process of these changes, gives us an indication of some of the points of contention.

56% of admins felt that academics are not sufficiently accountable for their worktime (p.167)

“A mere 12% of academics thought their research productivity had increased as a result of formal appraisal processes, and 57% clearly thought not” (p.167)

“41% of administrators believing that quality assurance mechanisms would ensure genuine improvement to the higher education system as against 19% of academics” (p.167)

67% of academics (vs 52% of admins) felt that “universities are of little value to society if they are not autonomous” (p.166)

Much of McInnis’ paper revolves around the impact these changes have on the “core values” (p.170) of the academy, going so far as to conclude that

“Efficiency and effectiveness, productivity and performance, accountability and supervision are typically the preoccupation of administrators. It may be argued that the growth in specialist support staff and administrators such as experts in marketing, counselling and strategic planning has amounted to a subtle process of ‘colonisation’ of higher education. The experts are assumed to bring with them market and individualistic values with no particular allegiance to the higher-order goals of the academic world” (p.171)

I find it interesting that these core values and higher-order goals are never explicitly stated – presumably as an academic you just ‘get’ them but autonomy seems to sit firmly at the core.

(This shouldn’t be taken to suggest that I believe that Higher Education and research should be treated as businesses in place of of noncommercial exploration, investigation and creativity, it’s more that the underlying assumptions that “non-academics” exist only in a soulless world of spreadsheets seems narrow minded and perhaps a little arrogant.)

McInnis makes his most explicit statement of this in his conclusion:

“where once administrative staff were considered powerless functionaries, they now increasingly assume high-profile technical and specialist roles that impinge directly on academic autonomy and control of the core activities of teaching and research” (p.170)

Looking at power reveals another significant source of tension in the academic/professional staff binary – rightly or wrongly. It’s hardly a new thing however.

Szekeres observes that

“Lee and Bowen (1971) found that academics tended to confound the lives of administrators but at the same time they vastly over-estimated the power that administrators had” (p.19)

A key point that often seems to be missed is that while professional / administrative staff are often responsible for implementing changes seen as less desirable by academics, these have almost always come from the university executive – Deans, Vice Chancellors and the like – who are invariably academics. Dobson notes that

“too few staff (particularly academic staff) understand or appreciate the reality of university authority structures. The ills which have befallen universities in recent times have frequently been seen by the academic staff as the fault of ‘the administration’. The difference between ‘administration’ and ‘governance’ seems to be lost on many members of the academic staff. That there is an ‘attitude problem’ toward the role of general staff among some in the academic ranks in exemplified by the following quote from Cullen (1988):

“There is a great deal of talent in the academic staff of higher education institutions. How they manage the systems which surround them and still find time to make a contribution to academic programs is a minor miracle… there is an old adage that administration is too important to be left to the administrators. It seems to me that this is certainly true of the sorts of reforms [in the Green and White Papers] we now need to discuss (p.154)” “ (p.208 of Dobson)

Academics can be even more scathing of former academics in the university executive levels than of professional / administrative staff. Szekeres found a quote in a Academia Nuts, a satirical novel about university life by Michael Wilding describing them thusly:

“they are not even trained administrators, they are not even professional managers. They are the Judases of the profession (2002, p.202)” (p.14)

So perhaps it is as much a matter of expressing frustration at anybody who gets in the way and being unable to sort the ‘functionaries’ from the ‘Judases’.

In practical terms however, the perception of a shift in power to professional staff may be over estimated. Three quotes from the comments sections of the survey of administrative staff reviewed by McInnis are revealing.

“in order for an opinion to be accepted it seems it must be sanctioned by an academic – this is very frustrating for general staff who are experts in their field” (p.168)

“the current concept of ‘general’ or ‘administrative’ staff inherently denies that we have specialist skills or subject expertise” (p.168)

“there is little recognition that there are highly qualified and experienced professionals in areas of support expertise which the University now needs and that they may well be better able to manage these tasks better than an academic; the assumption that an academic specialisation in a field makes a practising expert e.g. in marketing; or that computing support needs ultimately to be managed by an academic (Director of unit)” (p.168-9)

On the Professional staff side, by far the most significant issue reported (repeatedly) was the lack of respect or appreciation for their work from academic staff. According to McInnis

“only 28% of administrators agreed that ‘the relationship between academic and general staff is generally very positive’ and 36% expressed dissatisfaction with the appreciation their roles by academic staff” (p.167)

The under-representation of professional staff in publications about Higher Education, could be seen as another symptom of this and even the authors of these papers that appear more sympathetic to their plight sometimes pay more ‘backhanded compliments’

“It is probably fair to say that most general staff both ‘know their place’ and realise that their role is not the ‘main game’, but perhaps some academic staff haven’t caught up with the fact that a professional general staff does much to support and to enhance the student experience at university” (Dobson, p.209)

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, the three authors generally all come to the same conclusions, recognising that there is no option to put the genie of recent Higher Education reform back in the bottle and that more understanding and effective collaboration is needed between academic and professional staff.

With Szekeres’ attention being primarily on the representation of professional staff in current literature relating to Higher Education, she feels that much more effort needs to be put into telling and understanding “the stories of administrative staff” (p. 20).

She is fairly scathing of current representations

“much of the writing about universities which has emanated from the academic community has displayed erroneous perceptions. Many of these writers have been dismissive of administrative staff and their roles in the institution or have ignored them altogether. When provided at all, many of the constructions of academic staff demonstrate false impressions of what administrators actually do, the nature of their work and their relationship to the organisation” (p.20)

McInnis, on the other hand, makes it clear in his conclusion that he believes that this needs to done with an emphasis on the traditional values of academia

“the extent to which administrative staff support core values is crucial to the preservation of university autonomy” (p.170)

and

“the key question is how to support and sustain the transformation of universities while acknowledging and accommodating the basic sentiments and work practices of academics considered central to the idea of the university as a community of learners” (p.171)

Dobson ends with an appeal for understanding from academic staff that unfortunately somewhat downplays professional staff concerns about being being disrespected and unappreciated but which broadly calls for unity

“Should general staff be worried by the attitudes of some academic staff members? Probably not, because they will have found that there are also many rude people among the senior general staff. However, this does not change the fact that there is a need for a greater understanding by academic staff that the changes in higher education have been difficult for general staff too” (p. 210)

Many of these issues I’d have to put into the university-culture basket (the “too-hard basket”?) because there are a lot of long established and entrenched attitudes and expectations that are unlikely to change quickly. Speaking openly about them, sharing stories and viewpoints and increasing understanding at least seems like a useful first step.

2977232

GETJ9CEB,NB6P2UBK,42SQA6BD

items

1

apa

0

default

asc

778

https://www.gamerlearner.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3A%22zotpress-6f9256bef0e9bd362aa898896feb0e0a%22%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%2242SQA6BD%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2977232%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Szekeres%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222004-03-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A6%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESzekeres%2C%20J.%20%282004%29.%20The%20invisible%20workers.%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Higher%20Education%20Policy%20and%20Management%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E26%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%281%29%2C%207%26%23x2013%3B22.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F1360080042000182500%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F1360080042000182500%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20invisible%20workers%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Judy%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Szekeres%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Where%20are%20university%20administrators%20placed%20in%20texts%20that%20are%20centred%20around%20universities%3F%20There%20appears%20to%20be%20either%20a%20total%20confusion%20in%20terminology%20about%20administration%20or%20a%20complete%20disregard%20for%20administrators%27%20work%20but%20in%20most%20cases%20administrative%20staff%20in%20universities%20are%20largely%20invisible.%20This%20paper%20explores%20a%20range%20of%20texts%20%28academic%2C%20government%20reports%20and%20novels%29%20and%20provides%20a%20picture%20of%20how%20the%20work%20of%20administrators%20and%20the%20staff%20themselves%20are%20represented.%20It%20examines%20how%20they%20are%20positioned%20in%20the%20organisation%20as%20people%2C%20as%20workers%20and%20as%20power%20brokers%20and%20provides%20a%20starting%20point%20for%20further%20research%20into%20how%20these%20workers%20see%20themselves.%20%5Cu201cThere%20has%20been%20remarkably%20little%20systematic%20study%20of%20the%20roles%20and%20values%20of%20university%20administrative%20staff%5Cu201d%20%28McInnis%2C%201998%2C%20p.%20161%29.%20Maybe%20it%20is%20time%20that%20this%20was%20remedied.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22March%201%2C%202004%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1080%5C%2F1360080042000182500%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221360-080X%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdx.doi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F1360080042000182500%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22NSAT4XC7%22%2C%22ZR5S4RUA%22%2C%22AFLLUJ4K%22%2C%229AVIUSDZ%22%2C%22B7DWPBS2%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-27T02%3A47%3A27Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22NB6P2UBK%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A2977232%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Dobson%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222000-11-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A6%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EDobson%2C%20I.%20R.%20%282000%29.%20%26%23x201C%3BThem%20and%20Us%26%23x201D%3B%20-%20General%20and%20Non-General%20Staff%20in%20Higher%20Education.%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Higher%20Education%20Policy%20and%20Management%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ci%3E22%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%282%29%2C%20203%26%23x2013%3B210.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F713678142%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdoi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F713678142%3C%5C%2Fa%3E%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22%27Them%20and%20Us%27%20-%20General%20and%20Non-General%20Staff%20in%20Higher%20Education%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ian%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Dobson%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22This%20paper%20examines%20aspects%20of%20the%20%27binary%20divide%27%20in%20Australian%20higher%20education%20staffing%2C%20looking%20at%20the%20role%20of%20general%20staff%20in%20tertiary%20education%20administration%20and%20management%20in%20the%201990s%2C%20and%20the%20antipathy%20many%20members%20of%20academic%20community%20appear%20to%20have%20toward%20general%20staff.%20There%20are%20brief%20comparisons%20with%20the%20situation%20in%20three%20other%20countries%2C%20the%20United%20Kingdom%2C%20the%20Netherlands%20and%20Finland%20which%20provide%20a%20point%20of%20comparison%20with%20the%20Australian%20situation.%20This%20report%20was%20prepared%20as%20an%20outcome%20both%20of%20research%20into%20the%20Australian%20situation%20and%20an%20overseas%20visit%20funded%20by%20an%20ATEM%20International%20Travel%20Grant%20in%201998.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22November%201%2C%202000%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%2210.1080%5C%2F713678142%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221360-080X%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdx.doi.org%5C%2F10.1080%5C%2F713678142%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22NSAT4XC7%22%2C%22ZR5S4RUA%22%2C%229AVIUSDZ%22%2C%22B7DWPBS2%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222018-06-27T02%3A39%3A27Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D

Szekeres, J. (2004). The invisible workers.

Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,

26(1), 7–22.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080042000182500

Dobson, I. R. (2000). “Them and Us” - General and Non-General Staff in Higher Education.

Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,

22(2), 203–210.

https://doi.org/10.1080/713678142