This is a big post because it is about a journal article that covers some of the core issues of my thesis in progress. I’ve spent far longer looking over, dissecting and running off on a dozen tangents with it than I had expected. My highlights and scrawled notes are testament to that.

In a nutshell, King and Boyatt attribute the success (or otherwise) of adoption of e-learning in their university to three key factors. Institutional infrastructure, teacher attitudes and knowledge and perceived student expectations. This seems like a reasonable argument to make and they back it up with some fairly compelling arguments that I’ll expand on and provide my own responses to shortly.

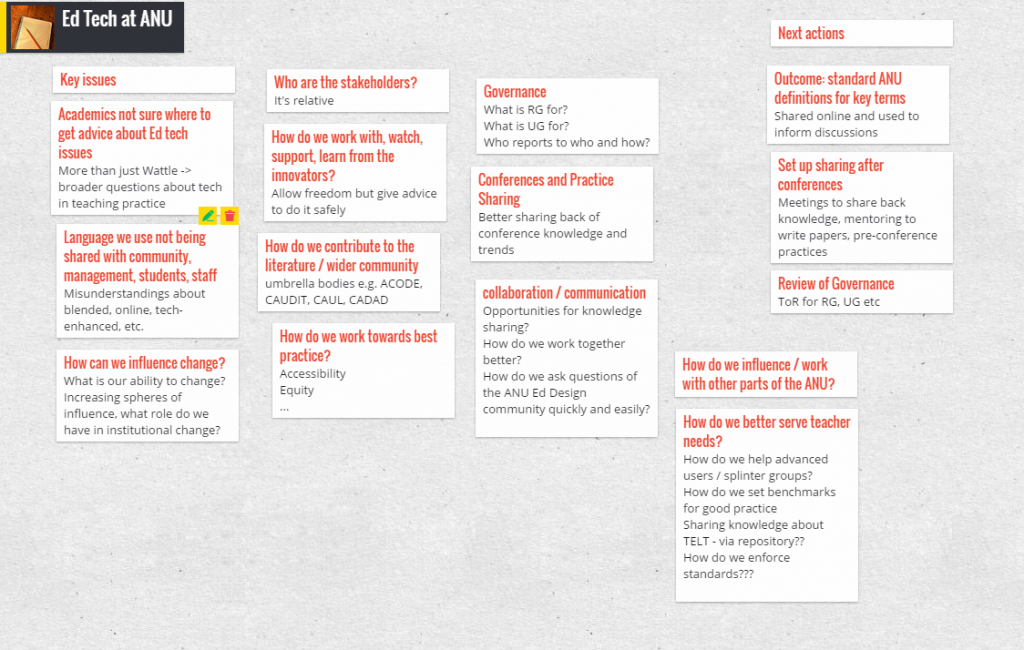

They use this to generate a proposed action plan which includes a coherent and detailed university level e-learning strategy – which includes adequate resourcing for technological and pedagogical support, academic development training, leadership, guidance, flexibility and local autonomy. Everything that they propose seems reasonable and sane yet (sadly) quite optimistic and ambitious. From their bios, I think that the authors aren’t teachers themselves but education advisors like myself but the perspective put forward in the article is very clearly from an academic’s perspective. (Well, 48 academics from a range of discplines, ages and years of teaching experience.) All the same, there were more than a few occasions when I read the paper and thought – “well it’s fine to suggest communities of practice (or whatever) but even when we do set them up, nobody comes more than once or twice”.

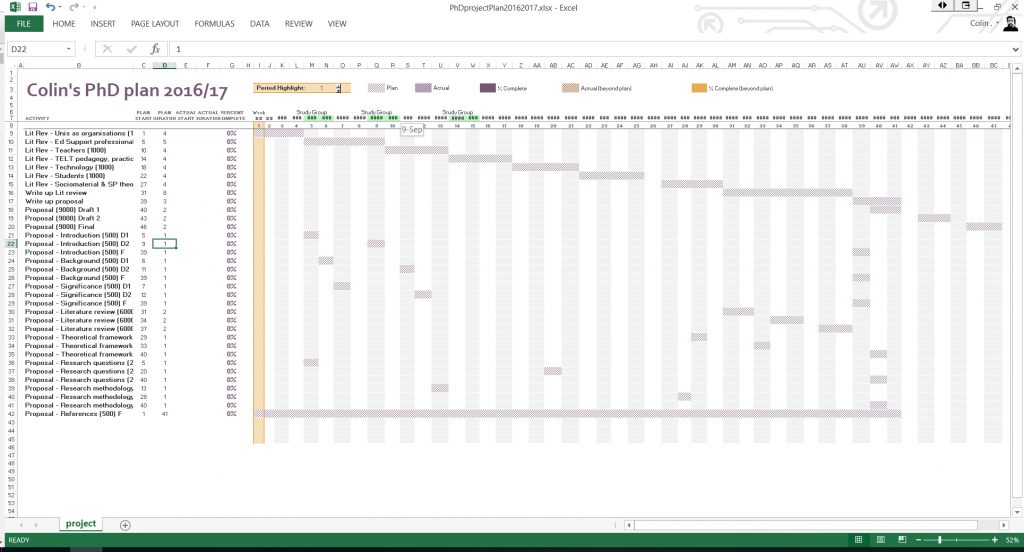

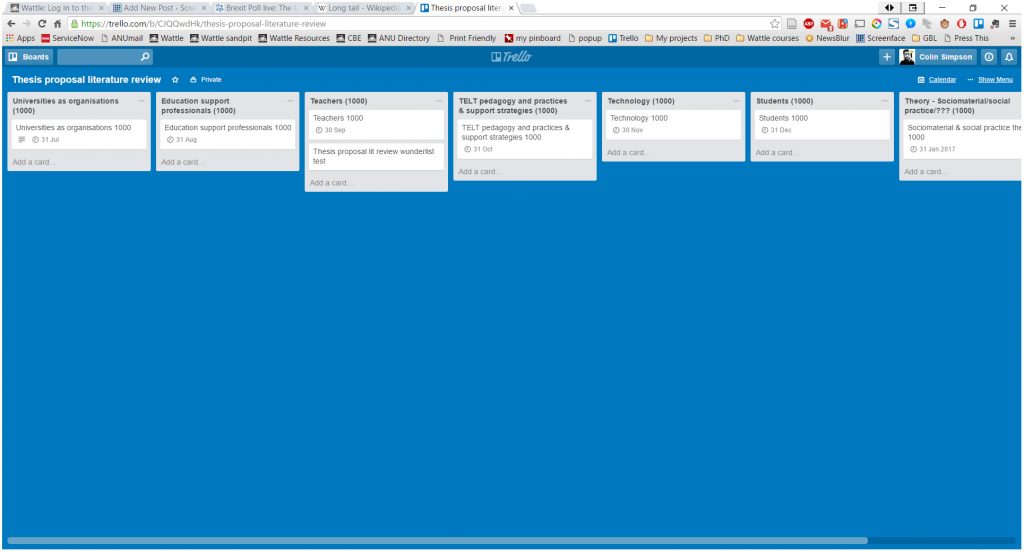

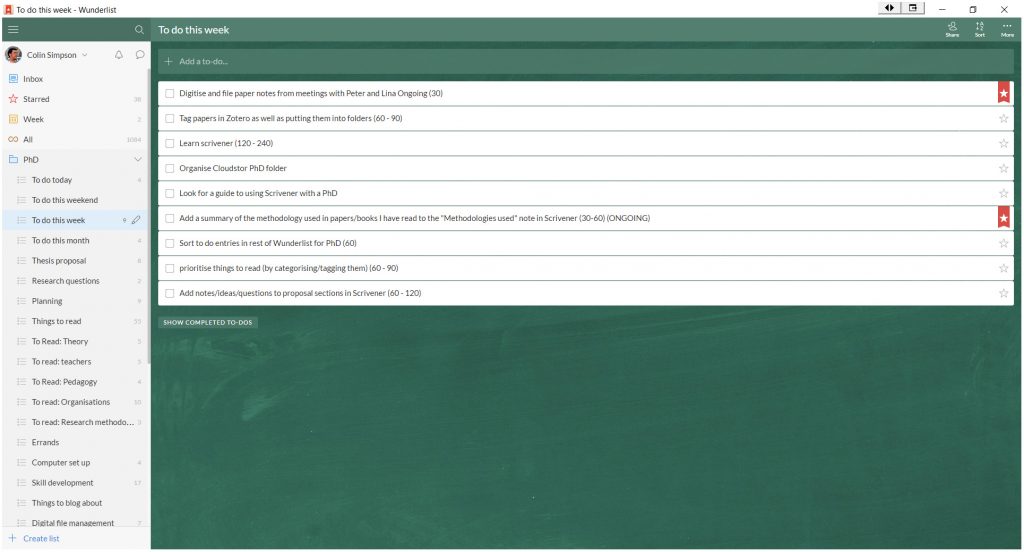

I guess the main difference between this paper and my line of thinking in my research is that I want to know what gets in the way, and I didn’t get enough of that here. I also found myself thinking a few times that this kind of research needs to avoid falling into the trap of forgetting that teaching is only one (often de-prioritised, depending on the uni culture) part of an academic’s practice and we need to factor in the impact that their research and service obligations have on their ability to find time to do this extra training. To be completely fair though, the authors did recognise and note this later in the paper, as well as the fact that the section on perceived student expectations was only that – perceptions – and not necessarily a true representation of what students think or want. So they propose extending the study to include students and the university leadership, which seems pretty solid to me and helps to strengthen my personal view that this is probably a thing I’ll need to do when I start my own research. (I’m still in proposal/literature review/exploration swampland for now). To this I would probably add the affordances of the technology itself and also the Education Advisor/Support staff that can and would help drive much of this.

This paper sparked a number of ideas for me but perhaps the most striking was the question of what are the real or main reasons for implementing e-learning and TELT? Is it simply because it can offer the students a richer and more flexible learning experience or is it because it makes a teacher’s life easier or brings some prestige to a university (e.g. MOOCs) or (in the worst and wrongest case) is perceived as a cost-saving measure. There is no reason that it can’t be all of these things (and more) and that makes a lot of sense but some of the quotes from teachers in the article do indicate that they are more motivated to adopt new tools and teaching approaches if they can see an immediate, basically cost-free benefit to themselves. Again, I’m not unsympathetic to this – everyone is busy and if you’re under pressure to output research above all else, it’s perfectly human to do this. But it speaks volumes firstly about the larger cultural questions that we must factor in to explorations of this nature and secondly about the strategic approaches that we might want to take in achieving the best buy in.

From here, I’ll include the notes that I took that go into more specifics and also include some quotes. They’re a little dot pointy but I think still valuable. This is most definitely a paper worth checking out though and I have found it incredibly useful, even if I was occasionally frustrated by the lack of practical detail about successfully implementing the strategies.

“In addition, the results suggest that underpinning staff motivation to adopt e-learning is their broader interest in teaching and learning. This implies a bigger challenge for the institution, balancing the priorities of research and teaching, which may require much more detailed exploration” (p.1278)

Glad to see this acknowledged.

This paper focuses on Adoption. What are the other two phases in the Ako paper?

Initiation (a.k.a adoption), Implementation and Institutionalisation

Getting people to start using something is a good start but without a long term plan and support structure, it’s easy for a project to collapse. The more projects collapse, the more dubious people will be when a new one comes along.

Feel like there are significant contradictions in this paper – need for central direction/strategy as well as academic autonomy. Providing people with a menu of options is good and makes sense but that makes for huge and disparate strategy.

The three core influencing factors identified. (How well are they defined?)

Institutional infrastructure

Definition:

Includes: institutional strategy, sufficient resources (to do what?), guidance for effective implementation.

Question of academic development training is framed with limited understanding of the practicalities of implementation. Assumption that more resources can simply be found and allocated with no reciprocal responsibilities to participate.

Support needs identified:

Exploration of available tools and the development of the skills to use them

Creating resources/activities and piloting them

Developing student skills in using the tools

Engaging with students in synchronous and asynchronous activities

Monitoring and updating resources

Unclear over what time frame this support is envisioned. Presumably it should be ongoing, which would necessitate a reconsideration of current support practices.

“Participants suggested the need for a more coordinated approach. A starting point for this would be consideration of how available technologies might be effectively integrated with existing pedagogic practices and systems” (p.1275)

Issues basically boil down to leadership and time/resourcing. Teachers seem to want a lot in this space – “participants in this study reported the lack of a coherent institutional-wide approach offering the guidance, resources and recognition necessary to encourage and support staff.” At the same time, they expect “ongoing consultation and collaboration with staff to ensure a more coherent approach to meet institutional needs” (both p.1277).

If you want leadership but you also want to drive the process, what do you see leadership as providing? I do sympathise, this largely looks more like a reaction to not feeling adequately consulted with however my experience with many consultation attempts in this space is that very few people actually contribute or engage. (This could possibly be a good question to ask – phrased gently – what actions have you taken to participate in existing consultation and collaboration processes in ed tech)

“A further barrier to institutional adoption was the piecemeal approach to availability of technologies across the institution. Participants reported the need for a more coordinated approach to provision of technologies and their integration with existing systems and practices” (p.1277)

Probably right, clashes with their other requests for an approach that reflects the different disciplinary needs in the uni. How do we marry the two? How much flexibility is reasonable to ask of teachers?

Staff attitudes and skills

Definition:

Is this where “culture” lives?

Includes:

“including their skills and confidence in using the technology” (p.1275)

“A key step for broadening engagement is supporting staff to recognise the affordances of technology and how it might help them to maintain a high-quality learning experience for their students.

[teacher quote] There’s a lot of resistance to technology but if you can demonstrate something that’s going to reduce amount of time or genuinely going to make life easier then fine” (p.1275)

Want to know more about the tech can do – a question here is, for who. Making teaching easier or making learning better? Quote suggests the former.

What about their knowledge of ePedagogy? (I need to see what is in the Goodyear paper about competencies for teachers using eLearning. Be interesting to compare that to the Training Packages relating to eLearning too)

A big question I have, particularly when considering attitudes relating to insecurity and not knowing things – which some people will be reluctant to admit and instead find other excuses/reasons for avoiding Ed Tech (”it’s clunky” etc) – is how we can get past these and uncover peoples’ real reasons. It seems like a lot of this research is content to take what teachers say at face value and I suspect that this means that the genuine underlying issues are seldom addressed or resolved. There are also times when the attitudes can lead to poor behaviour – rudeness or abruptly dropping out of a discussion. (Most teachers are fine but it is a question of professionalism and entitlement, which can come back to culture)

In terms of addressing staff confidence, scaffolded academic dev training, with clear indicators of progress, might be valuable here. (Smart evidence – STELLAR eportfolios – Core competencies for e-teaching and some elective/specialisation units? This is basically rebuilding academic development at the ANU from the ground up)

“The findings highlighted the importance of a pedagogic-driven approach to implementation that supports staff in recognising the potential of technology to add value to students’ learning experiences. While staff recognised that support was available centrally, they suggested that it needed to be more closely tailored to the specific needs of staff and extended to include online guidance at point of need and communities of practice that facilitated sharing between colleagues” (p.1278)

These seems to strengthen the case for college/school level teams. I am well aware that teachers tend not to engage with academic development activities and resources outside their discipline area – which I think is partially tribal because the Bennett literature suggests that there are actually few differences in teaching design approaches from discipline to discipline. This seems like a good area for further investigation. What kind of research has been conducted into effectiveness (or desire for) centralised Academic Dev units vs those at a college level?

Perceived student expectations

Definition: Students expect their online learning world to match the rest of their online experiences.

“One student expectation reported was the availability of digital resources accessible anytime and anywhere: participants suggested that students expected to access all course materials online including resources used as part of face-to-face sessions and supplementary resources necessary to complete assignments.” (p.1276)

Seems like there are a lot of (admittedly informed) assumptions be made of what students actually want by the teachers in this section. Maybe it is reasonable to say that everyone wants everything to be easier. But when does it become too much easier? When they don’t need to learn how to research?

Student need to learn how to e-Learn

“These findings suggest that for successful implementation of e-learning, students need to be supported to develop realistic expectations, an understanding of the implications of learning with technology and skills for engaging in these new ways of learning and make the most out of the opportunities that they present” (p.1277)

Interestingly phrased outcome – DO students need to learn more about the challenges of teaching and/or the mechanisms behind it? Is this just about teachers avoiding responsibilities? It sounds a bit like being expected to study physics or road-building before going for a drive.

“However students confidence with online tools and resources was perceived to vary and the finding suggest that students need to be supported to develop skills to engage effectively with the opportunities that e-learning affords…

It is not clear whether this is an accurate portrayal of student views or whether staff attributed their own views to the students. It would be valuable to ascertain whether this perception is a true representation by repeating the study with students.” (p.1278)

Again, nice work by the authors in catching the difference between student perspectives and teacher assumptions. I guess the important part is that whether the students hold the views or not, the teachers believe they do and this motivates them to use the technology.

Students don’t want to lose F2F experiences and they don’t want eLearning forced upon them when it seems like a cost-cutting measure. They do want (and expect) resources to be available online.

Outcomes

Proposed elearning strategy

“Reflecting on the factors that influenced the adoption of e-learning, participants suggested the need for an institutional strategy that :

Defines e-learning

Provides a rationale for its use

Sets clear expectations for staff and students

Models the use of innovative teaching methods

Provides frameworks for implementation that recognise different disciplinary contexts

Demonstrates institutional investment for the development of e-learning

Offers staff appropriate support to develop their skills and understanding” (p.1277)

I’d add an additional item – Offers staff appropriate support to develop and deliver resources and learning activities in TELT systems.

I have a lot of questions about this strategy – what kinds of expectations are we talking about? Is this about the practical realities of implementing and supporting tools/systems which recognises limits to their affordances? Modelling the use of innovative teaching practices – just because something is new doesn’t mean that it is good. I’d avoid this term in favour of best practice and/or emerging. Is modelling really a valid part of a strategy or would it be more about including modelling/showcasing as one of the activities that will achieve the goals. The goals, incidentally, aren’t even referred to. (Other than the rationale but I suspect that isn’t the intent of that item)

Overall I think this strategy is an ok start but I would prefer a more holistic model that also factors in other areas of the academics responsibilities in research and service. The use of “e-learning” here is problematic and largely undefined. There’s just an assumption that everyone knows what it is and takes a common view. (Which is why TELT is perhaps a better term – though I still need to spend some time explaining what I – and the literature – see TELT as)

Support:

Face to face support complemented by online guidance (in what form?)

Facilitated CoPs to support academics sharing their experiences. (Can we anonymise these?? – visible only to teachers (not even exec). If one of our problems is that people don’t like to admit that they don’t know something, let them do it without people knowing. )

Wider marketing of support services in this space to academics. (I don’t buy this – I think that teachers get over marketed to now by all sections of the university and I’ve sent out a lot of info about training and support opportunities that get no response at all)

Faculty or departmental e-learning champion (Is that me or does it need to be an academic? Should we put the entire focus onto one person or have a community. Maybe a community with identifiable (and searchable) areas of expertise

Big question – how many people use the support that is currently available and why/why not?

My questions and ideas about the paper:

Demographics of the sample reasonably well spread – even genders, every faculty, wide distribution of age and teaching experience as well as use of TELT. No mention of whether any of the participants are casual staff members, which seems an important factor.

It’s fine to look at teaching practices but teaching doesn’t exist in a vacuum for academics. They also have research and service responsibilities and I think it would be valuable to factor the importance of these things in the research. The fact that nobody mentions them – or time constraints – suggests that they weren’t part of the focus group or interview discussions.

My overall take on this – the authors expand on previous work by Hardaker and Singh 2011 by adding student expectations to the mix. I’d think there is also a need to consider the affordances of existing technology (and pedagogy?) and perhaps also a more holistic view of the other pressure factors impacting teachers and the university.

“The findings highlighted the importance of a pedagogic-driven approach to implementation that supports staff in recognising the potential of technology to add value to students’ learning experiences.” (p.1278)

There are a lot of reasons that TELT is actually implemented in unis and while this might be the claim as the highest priority, I would be surprised if it made the top 5. Making life easier for the uni and for teachers, compliance, cost-cutting, prestige/keeping-up-with-the-Joneses and canny vendors all seem quite influential in this space as well. Understanding how the decisions driving TELT implementations are made seems really important.

King, E., & Boyatt, R. (2015). Exploring factors that influence adoption of e-learning within higher education: Factors that influence adoption of e-learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(6), 1272–1280. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12195