I was recently invited by @UQKelly – Kelly Matthews of the University of Queensland – to attend the National Students as Partners Roundtable on a glorious Brisbane Spring day. (For which I am grateful almost as much for the chance to escape a particularly bleak Canberra day as for the exposure to some interesting ideas and wonderful people working in this space). This isn’t an area that I’ve had much to do with and I was invited to bring a critical friend/outsider perspective to proceedings as much as anything.

Students as Partners (which I’ll shorten to SaP because I’ll be saying it a lot) more than anything represents a philosophical shift in our approach to Higher Education, it doesn’t seem like too great a stretch to suggest that it almost has political undertones. These aren’t overt or necessarily conventional Left vs Right politics but more of a push-back against a consumerist approach to education that sees students as passive recipients in favour of the development of a wider community of scholarship that sees students as active co-constructors of their learning.

It involves having genuine input from students in a range of aspects of university life, from assessment design to course and programme design and even aspects of university governance and policy. SaP is described as more of a process than a product – which is probably the first place that it bumps up against the more managerialist model. How do you attach a KPI to SaP engagement? What are the measurable outcomes in a change of culture?

The event itself walked the walk. Attendance was an even mixture of professional education advisor staff and academics and I’d say around 40% students. Students also featured prominently as speakers though academics did still tend to take more of the time as they had perhaps more to say in terms of underlying theory and describing implementations. I’m not positive but I think that this event was academic initiated and I’m curious what a student initiated and owned event might have looked like. None of this is to downplay the valuable contributions of the students, it’s more of an observation perhaps about the unavoidable power dynamics in a situation such as this.

From what I can see, while these projects are about breaking down barriers, they often tend to be initiated by academics – presumably because students might struggle to get traction in implementing change of this kind without their support and students might not feel that they have the right to ask. Clearly many students feel comfortable raising complaints with their lecturers about specific issues in their courses but suggesting a formalised process for change and enhancements is much bigger step to take.

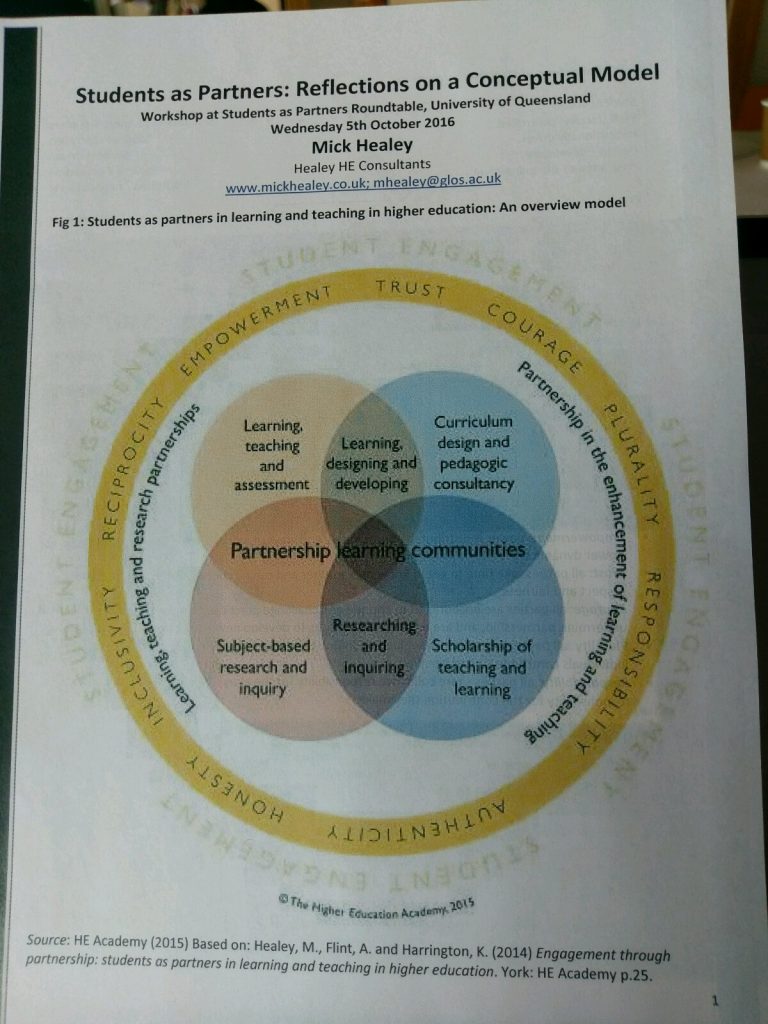

The benefits of an SaP approach are many and varied. It can help students to better understand what they are doing and what they should be doing in Higher Education. It can give them new insights into how H.E. works (be careful what you wish for) and help to humanise both the institution and the teachers. SaP offers contribution over participation and can lead to greater engagement and the design of better assessment. After all, students will generally have more of a whole of program/degree perspective than most of their lecturers and a greater understanding of what they want to get out of their studies. (The question of whether this is the same as what they need to get out of their studies is not one to ignore however and I’ll come back to this). For the students that are less engaged in this process, at the very least the extra time spent discussing their assessments will help them to understand the assessments better. A final benefit of actively participating in the SaP process for students is the extra skills that they might develop. Mick Healey developed this map of different facets of teaching and learning that it enables students to engage with. A suggestion was made that this could be mapped to more tangible general workplace skills, which I think has some merit.

As with all things, there are also risks in SaP that should be considered. How do we know that the students that participate in the process are representative? Several of the students present came from student politics, which doesn’t diminish their interest or contribution but I’d say that it’s reasonable to note that they are probably more self-motivated and also driven by a range of factors than some of their peers. When advocating for a particular approach in the classroom or assessment, will they unconsciously lean towards something that works best for them? (Which everyone does at some level in life). Will their expectations or timelines be practical? Another big question is what happens when students engage in the process but then have their contributions rejected – might this contribute to disillusionment and disengagement? (Presumably not if the process is managed well but people are complicated and there are many sensitivities in Higher Ed)

To return to my earlier point, while students might know what they want in teaching and learning, is it always what they need? Higher Ed can be a significant change from secondary education, with new freedoms and responsibility and new approaches to scholarship. Many students (and some academics) aren’t trained in pedagogy and don’t always know why some teaching approaches are valuable or what options are on the table. From a teaching perspective, questions of resistance from the university and extra time and effort being spent for unknown and unknowable outcomes should also be considered. None of these issues are insurmountable but need to be considered in planning to implement this approach.

Implementation was perhaps my biggest question when I came along to the Roundtable. How does this work in practice and what are the pitfalls to look out for. Fortunately there was a lot of experience in the room and some rich discussion about a range of projects that have been run at UQ, UTS, Deakin, UoW and other universities. At UoW, all education development grants must now include a SaP component. In terms of getting started, it can be worth looking at the practices that are already in place and what the next phase might be. Most if not all universities have some form of student evaluation survey. (This survey is, interestingly, an important part of the student/teacher power dynamic, with teachers giving students impactful marks on assessments and students reciprocating with course evaluations, which are taken very seriously by universities, particularly when they are bad).

A range of suggestions and observations for SaP implementations were offered, including:

- Trust is vital, keep your promises

- Different attitudes towards students as emerging professionals exist in different disciplines – implementing SaP in Law was challenging because content is more prescribed

- Try to avoid discussing SaP in ‘teacher-speak’ too much – use accessible, jargon-free language

- Uni policies will mean that some things are non negotiable

- Starting a discussion by focusing on what is working well and why is a good way to build trust that makes discussion of problems easier

- Ask the question of your students – what are you doing to maximise your learning

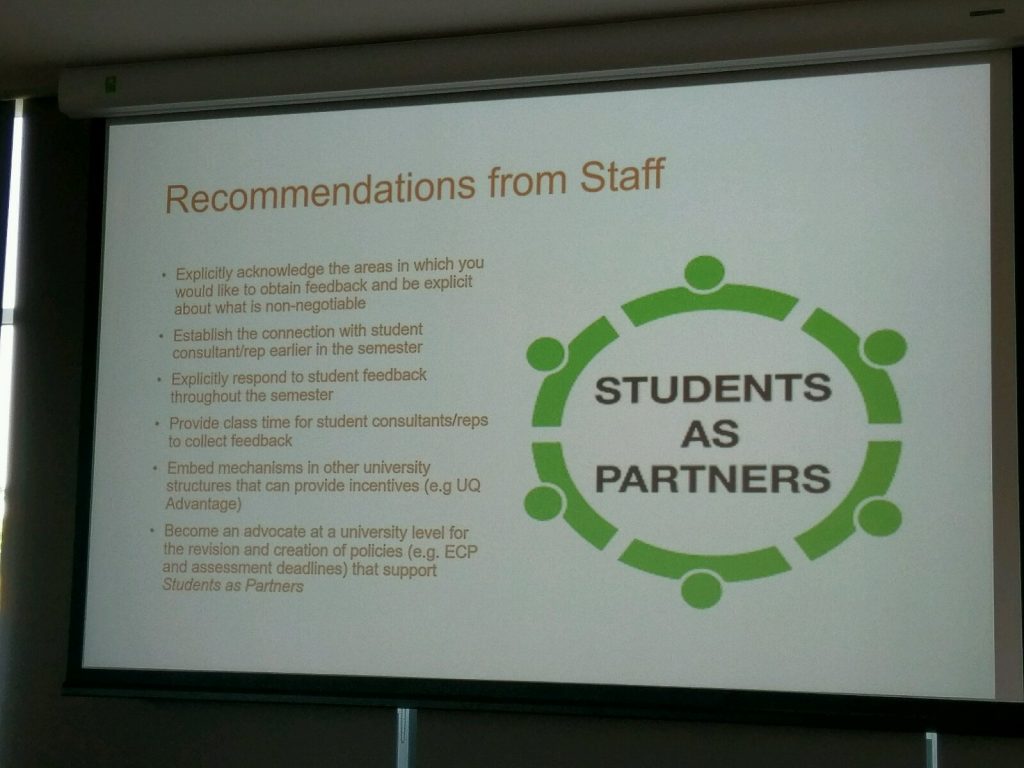

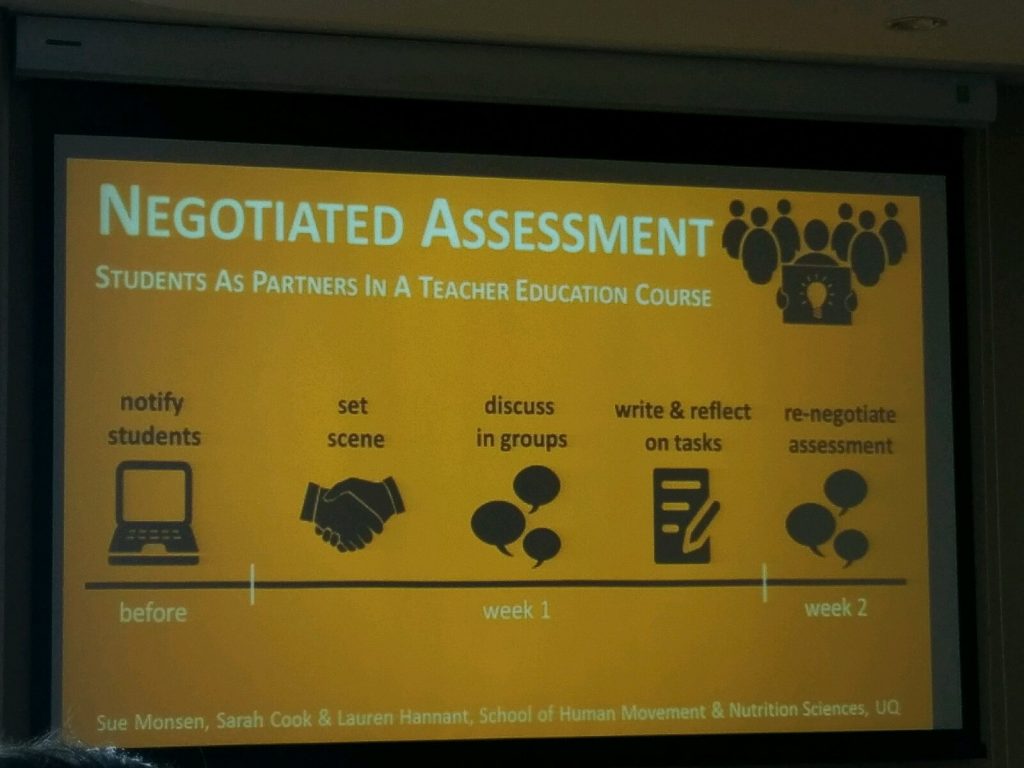

These images showcase a few more tips and a process for negotiated assessment.

There was a lot of energy and good will in the room as we discussed ideas and issues with SaP. The room was set up with a dozen large round tables holding 8-10 people each and there were frequent breaks for table discussions during the morning and then a series of ‘world cafe’ style discussions at tables in the afternoon. On a few occasions I was mindful that some teachers at the tables got slightly carried away in discussing what students want when there were actual, real students sitting relatively quietly at the same table, so I did what I could to ask the students themselves to share their thoughts on the matters. On the whole I felt a small degree of scepticism from some of the students present about the reality vs the ideology of the movement. Catching a taxi to the airport with a group of students afterwards was enlightening – they were in favour of SaP overall but wondered how supportive university executives truly were and how far they would let it go. One quote that stayed with me during the day as Eimear Enright shared her experiences was a cheeky comment she’d had from one of her students – “Miss, what are you going to be doing while we’re doing your job”

On the whole, I think that a Students as Partners approach to education has a lot to offer and it certainly aligns with my own views on transparency and inclusion in Higher Ed. I think there are still quite a few questions to be answered in terms of whether it is adequately representative and how much weighting the views of students (who are not trained either in the discipline or in education) should have. Clearly a reasonable amount but students study because they don’t know things and, particularly with undergraduate students, they don’t necessarily want to know what’s behind the curtain. The only way to resolve these questions is by putting things into practice and the work that is being done in this space is being done particularly well.

For a few extra resources, you might find these interesting.

International Journal for Students as Partners – https://mulpress.mcmaster.ca/ijsap

Students as Partners Australia network – http://itali.uq.edu.au/content/join-network

Student voice as risky praxis: democratising physical education teacher education

UTS Student voice in university decision making